The Windows

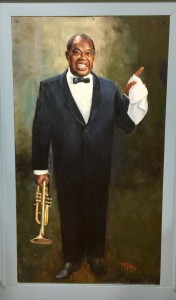

We had to figure out something to cover the seven foot high windows in the jazz museum, and curtains didn’t seem like the right approach. We decided on pictures, or paintings of some of the major players in the jazz trumpet world up to 1989. Finding a local artist we could afford and who was good was our dilemma, but where would we find him, or her?

I just happened to see a great portrait of Buddy Tate one day in Sherman in a frame shop while having some posters framed. Buddy Tate had been a great saxophone player from Sherman who had played in the Count Basie Orchestra. I asked the owner of the frame shop who did the painting because I knew I had found our artist to do our jazz paintings for us. The artist was a local woman who was well known and taught art lessons from her home named Pat Pierce. She was in her 70s, short, but I didn’t know if she wanted to take on a project such as ours. We would be needing 13 large paintings, just for starters. Plus, we needed them fairly fast, not in two years.

When Pat arrived at the museum to meet with us the first time, she immediately noticed a portrait of my great grandfather hanging in the lobby of the museum. To our surprise she recognized the artist’s work who had done the portrait of my great-grandfather. She told us she had been a young art student of the woman who had done the portrait! I thought that was impossible since my great grandfather died in 1919 and the portrait must have been done before that sometime. However, Pat had been a young woman when she took the lessons, while the artist who had painted my grandfather’s portrait was an older woman by the time she taught Pat.

It was this lineage of artists that made us sure we had found the right artist. If my great grandfather liked this woman’s style and she had taught Pat, then she was good enough for me. Pat and her husband, Jack, have felt like family to us since the day we met. I don’t know how we were lucky enough to find her, but it all fell into place like magic. She was the artist I had wanted to find, and her price was what I could afford while we were waiting to hear back from the IRS about my dad’s estate tax. The first 13 paintings she did for us was just the start, however. We still had two rooms downstairs which would require another 10, or 11 large paintings.

Mark Taylor’s Other Donations

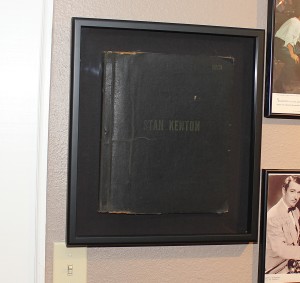

Along with the 2,200 albums Mark Taylor donated to our museum, there were two other major donations. His dad had been personal friends with Stan Kenton over the years, and had acquired the band crate and Stan’s personal music folder. These are great pieces of jazz history, and we are very happy to have them.

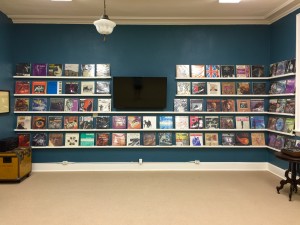

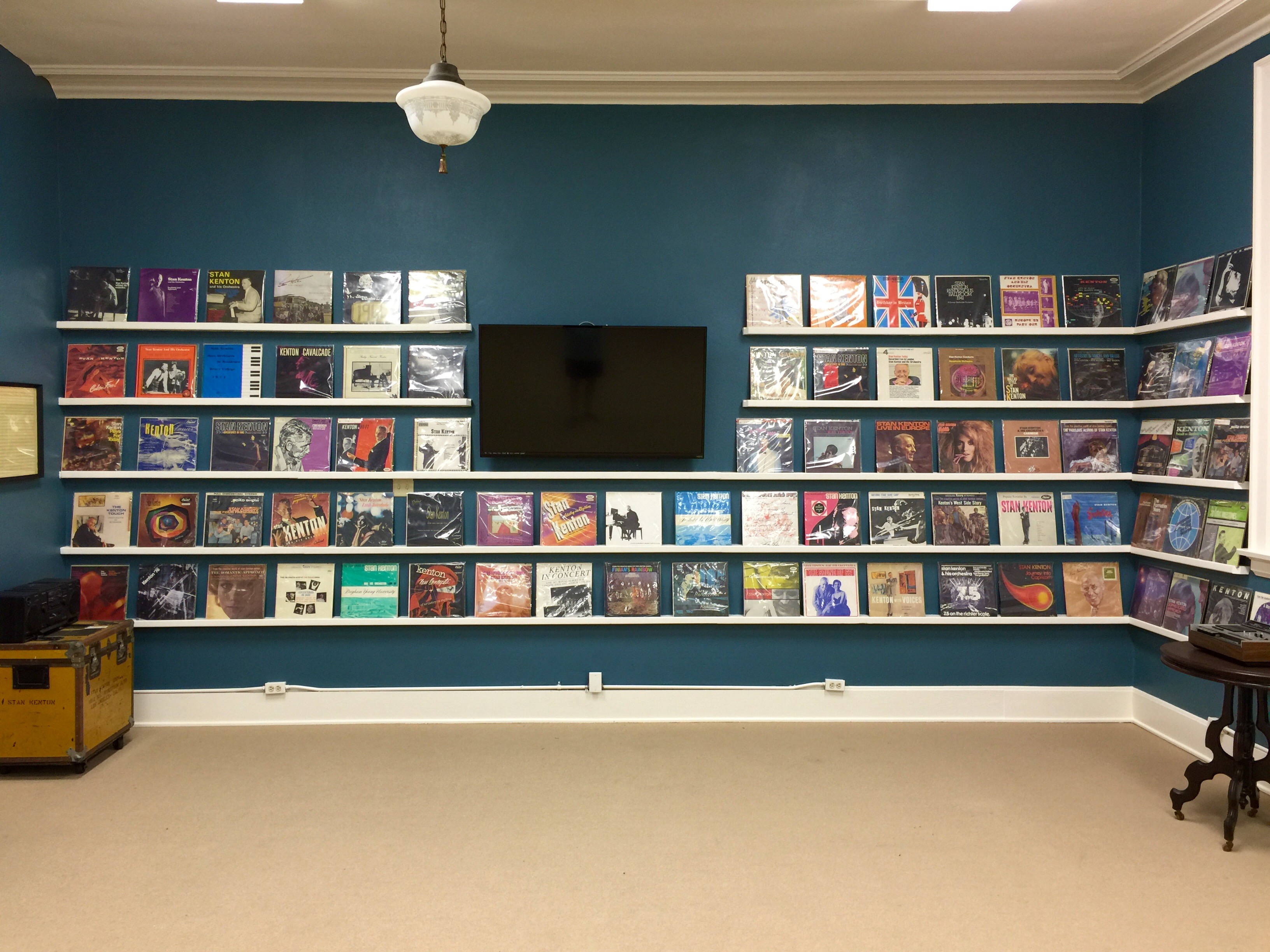

Our mission is not just jazz education, it’s jazz preservation. These are two good examples of jazz artifacts that belong in a museum. It’s things like this early on that got my attention that we could be something in addition to being a record album museum. Why not have Stan Kenton’s albums and also something from the band? In the Taylor collection we had all of the Kenton albums, both on Capital, and on the Creative World publications. On one wall of the museum we put together as many of Stan’s albums as we had room for, plus his crate off to the side. His music folder is nearby on a wall near the albums.

It is very impressive to me to see how many albums a Stan Kenton, or a Wood Herman, or others produced during their careers. It basically shows the lives of these men who lived their lives on the road. Many people, or libraries, have these albums but they are not likely on display as we have them. On the TV above the Kenton albums we can show Kenton YouTube videos, just to pull it all together. We couldn’t have done this without the Mark Taylor donation.

Two Major Donations of Record Albums

When I started working on the museum in October of 2005, I only had a few records of my own to put in the museum. Soon, however, we acquired 3,400 records in two donations from two of my friends.

Leonard Belota donated his entire record collection of about 1,200 albums to us as soon as he found out what we had in mind. He had collected mostly small group albums during his life, and it is a marvelous collection. He had no kids to leave the albums to, plus he could always come see his collection anytime. Because I had been collecting mostly big band albums during my life, his donation was a perfect fit.

Mark Taylor’s dad had been a jazz DJ in Ohio for ten years before he died and after he died, Mark offered his dad’s 2,200 albums to us. Mark and I had been students together at North Texas years before, and had remained friends through the years. His gift was beyond belief to me. All of a sudden we had a serious record album museum with some fantastic albums for people to see and examine. I was starting to see that the museum was taking shape on it’s own, as I stood by and watched how the universe worked.

I started to set up the museum in sections based on what we had. I decided to select several of the most important trumpet players, and showcase their albums. Each section had room for a different number of records, so the positioning of the players was based primarily on how many records I had of each player. However, I wanted Al Hirt next to Wynton because Al gave Wynton his first trumpet. I also wanted to mix the races as much as possible so people wouldn’t see any bias from me in any way. To musicians it’s all about the music and how you play, and that’s the attitude I wanted the museum to promote. It is the music I am trying to expose people to and any other agenda would not be accepted. If someone walked in as a fan of Maynard Ferguson, I wanted them to walk out with an interest in someone else, such as Miles Davis or Chet Baker. I wanted to show how many great players and jazz styles the jazz world possessed, just in the area of trumpet. I also wanted to show how the players are all connected in an evolutionary process. In the more modern players, you can hear many of the players who came before them. The early players influenced everyone who came along later, and, as you see the players on the walls, you can see that connection.

My thinking is that someone can spend an hour at the museum looking and listening to the many jazz players on display, and in that short time link a sound with a face. If they like a certain sound they hadn’t heard before, it will open up a new world of listening for them. That’s my idea for the museum, and it’s jazz education in a fun, easy approach. Maybe my two music education degrees will be of more use than I originally thought. My playing experience and my college experience finally started to make sense to me. The years of playing was not a dead end and the college education was not a waste of time and money. Having said that, most of my time running the museum is spent in the business world. Working for my dad part time for 28 years helping to manage his properties and investments also made sense. It is how the museum can survive long term, I hope.

Cat Anderson

William Alonzo Anderson, known as Cat Anderson (September 12, 1916-April 29, 1981), had a birthday two days ago. Cat became famous in the Duke Ellington Orchestra and was probably the best high note trumpet player in history.

I’ll never forget hearing the Ellington band in Ft. Worth in 1971, probably near the end of Cat’s tenure with the band. He was amazing with the upper register, but what stayed with me just as much was that he slept on the band stand sitting in his chair when not playing. I had never seen anyone do that before, or since. I wondered how he knew when to wake up and play, and I also wondered how he didn’t get fired. I leaned later in life that Duke was willing to put up with just about anything from his musicians–he was very loyal.

I don’t really remember much else about the concert that day. Cat’s playing was so impressive that I still can see and hear him playing “Satin Doll”. It was so effortless for him to do what very few could even come close to doing. I did read later in life, also, that Cat practiced four hours a day, both on off days and on performance days. I also heard from friends that he was very secretive about what size mouthpiece he played. I was told he would always take his mouthpiece with him on breaks. He was only 64 when he died. Now that I am 64 I can say that he died very young!